Reinvigoration of Salt Lake City’s remaining Japantown provides new opportunities for the future while honoring and remembering the past.

There’s a street in downtown Salt Lake City serving as an urban archive with generations of stories written in brick and concrete. Near the Salt Palace Convention Center and the Vivint Arena, it stretches from Second to Third West on 100 South, bookended by the Japanese Church of Christ and the Salt Lake Buddhist Temple—the remnants of a once-thriving Japantown chronicling the Japanese American community’s 100+-year fight to save the celebrated space and preserve their history.

The latest struggle to safeguard this community space began in 2018, when a development dubbed the West Quarter project was proposed and included frontage on the southwest portion of what had come to be named Japantown Street. The massive multi-use high-rise buildings are designed to host commercial and residential spaces, and they had reserved their trash, recycling, and loading docks for Japantown Street—relegating a portion of the block to a back alley. With involvement from the State, Salt Lake County, and the city, the project also included millions in public funding for a large parking structure.

“For Japanese Americans in Utah, it was painful history repeating itself,” says Jani Iwamoto BS’82, Utah state senator and former Salt Lake County Council member. Iwamoto was a founding member of the Japanese Community Preservation Committee in the early 2000s and has advocated for Japantown since. A coalition of public, private, and community stakeholders—including Iwamoto and other U alums you’ll hear from here—collaborated to improve the West Quarter project and made plans to revitalize and strengthen Japantown, looking for ways to honor the history of the neighborhood while transforming it into a pedestrian-friendly hub for festivals, celebrations, and Japanese-centered businesses.

Okage Sama De: ‘I Am Who I Am Because of You’

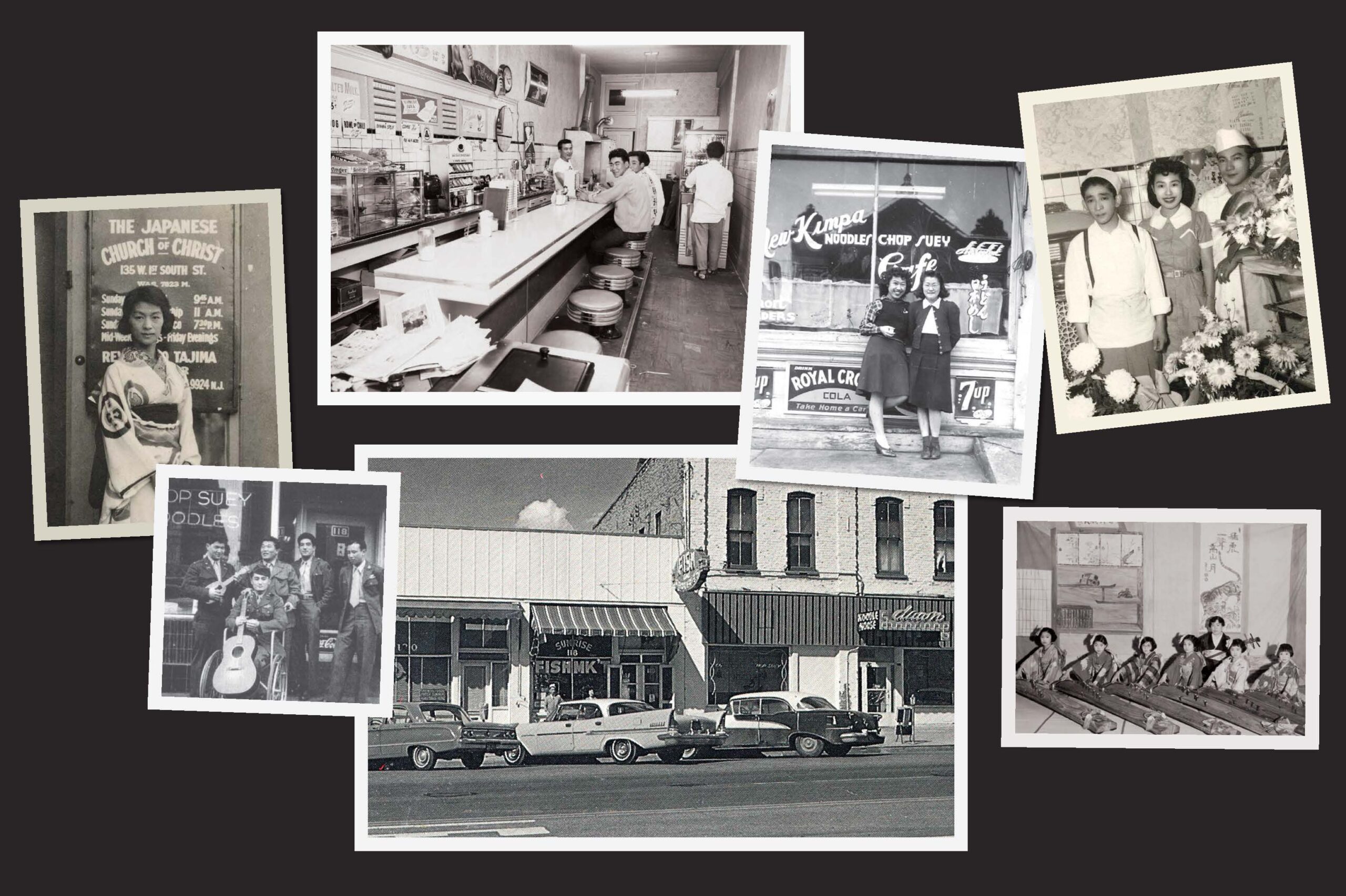

Japanese immigrants came to Utah primarily as railroad, agricultural, and mine workers in the late 1800s. In 1902, former railroad worker Edward Daigoro Hashimoto launched the E.D. Hashimoto Company near 100 South as a labor agency and to provide Japanese food, clothing, and other items and services that many Japanese residents sought. In less than a decade, more than 2,000 people of Japanese heritage had moved to the area. By 1925, the Japanese Church of Christ and the Buddhist temple were built where they still stand today. Dance studios, two newspapers, a Japanese language school, and other stores, restaurants, and gathering spaces sprawled across several blocks in what became known as Japantown.

The community changed drastically during and after World War II. President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942, relocating more than 120,000 West Coast Japanese Americans to internment camps, including to the Topaz War Relocation Center near Delta, Utah. Anti-Japanese sentiment and harassment rose dramatically, only increasing after many of those displaced from the West Coast relocated to Utah’s community. In the mid-1960s, two core blocks of Japantown were razed to build what would become the Salt Palace arena, and many business owners had to either close shop or move to other parts of the city. This was part of an urban renewal wave that gutted neighborhoods across the country—largely targeting communities of color.

“I’ve heard about Japantown from my parents and their friends my whole life. Everybody went there—it was thriving—but the Salt Lake arena decimated it,” says Iwamoto. “I’m happy that we can move forward, but it’s really important that we honor the past and the people that came before us who made Japantown.”

Iwamoto recalls attending a funeral for a friend of the family in Japantown and seeing the evidence of encroachment and disregard. “Semitrucks were in the middle of the road, and crates were scattered blocking everything,” she notes. “It’s not that our community is against development, but we were never part of the discussion, and it always impacts us negatively.”

In subsequent years the community continued to advocate for their space. The Salt Palace expansion in 1996 and the early 2000s spurred Iwamoto, Third District Court Judge Raymond Uno BS’55 JD’58 MSW’63, and others to form the Japanese Community Preservation Committee (JCPC). They led a coalition to mitigate negative impacts—including building gates to hide loading docks, and a Japanese garden as a safety buffer for increased semitruck traffic—and got this section of First South officially named “Japantown Street.” However, the expansion made its mark.

As Iwamoto and others envision the future of this important community space, they are guided by the Japanese saying Okage sama de, or “I am who I am because of you.” This fundamental tenet has steered efforts to create a space of remembrance and respect that thrives over time and is a place of inclusion.

—BY LISA POTTER | HISTORIC PHOTOS COURTESY OF SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, J. WILLARD MARRIOTT LIBRARY, THE UNIVERSITY OF UTAH